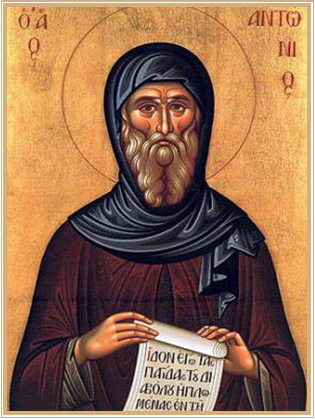

The Orthodox monastic life

Christian monasticism inaugurated by hermit St. Anthony of Egypt in 305, when he organized ascetic hermits in primitive monastic

communities, was continued by Anthony's disciple, Pachomius,

who introduced communal monastic life. Between 358-364, St. Basil drew up the rule that still governs Christian religious

communities, including the Orthodox Church. Both monks and

nuns are required to take vows of poverty, chastity, and

obedience, and to devote their lives to prayer and work. The goal

of this way of life is the achievement of personal salvation or

union with God through a continual spiritual battle with

temptation.

Monasticism spread quickly throughout the Byzantine Empire in the 4th-7th centuries, flourished in the 16th century in all Europe, and recorded a revival of interest in the 19th century.

Most monastics are imitators of Christ. Like Christ, they fast. Like Christ, they live the life of poverty, both in what they wear and what they possess. They do, therefore, spend time thinking about food and clothing, but this in the strange sense of thinking how best not to think of these.

They are careful not to eat that which invites gluttony or attachment to food, but to partake of the "daily bread" that provides for sustenance. They are worried about clothing that might move them away from the hem of the Savior's garment, which we all touch, entreating Christ to clothe them in His righteousness. And all of this monastics do for the very purpose of salvation. It is precisely the search for salvation which prompts them to be concerned about such things.

As Christ was obedient, so, too, the monastic is obedient. While some converts enter into the Orthodox monastic life wishing to reform the services and to discard this or that "typikon", most Orthodox monastics follow the typikon of their monastic superiors, linking themselves to an on-going succession of spiritual power that affects, indeed, the roots of salvation itself.

Orthodox monastic life involves a system which contemporary psychologists call a "feed-back loop." By attention to externals, we affect internals; and by the restored internal state, external attributes are affected. Endlessly linked to one another, internals and externals interact with one another to the point that they are no longer separate. The humble spirit manifests itself in the humble face; the sweet countenance in the sweetness of spirit; and the contrite heart within a contrite act. Grace brings what is inside out and what is outside in. Grace molds, blends, and transforms.

Unlike in Western Christianity, where sundry religious orders arose, each with its own profession rites, in the Eastern Orthodox Church, there is only one type of monasticism. The profession of monastics is known as Tonsure (referring to the ritual cutting of the monastic's hair which takes place during the service) and was, at one time, considered to be a Sacred Mystery (Sacrament). The Rite of Tonsure is printed in the Euchologion (Church Slavonic: Trebnik), the same book as the other Sacred Mysteries and services performed according to need, e.g., funerals, blessings, exorcisms, etc.

The monastic habit is the same throughout the Eastern Church (with certain slight regional variations), and it is the same for both monks and nuns. Each successive grade is given a portion of the habit, the full habit being worn only by those in the highest grade, known for that reason as the "Great Schema", or "Great Habit". One is free to enter any monastery of one's choice; but after being accepted by the abbot (or abbess) and making vows, one may not move from place to place without the blessing of one's ecclesiastical superior.

One becomes a monk or nun by being tonsured, a rite which only a priest can perform. This is typically done by the abbot. The priest tonsuring a monk or nun must himself be tonsured into the same or greater degree of monasticism that he is tonsuring into. In other words, only a hieromonk who has been tonsured into the Great Schema may himself tonsure a Schemamonk. A bishop, however, may tonsure into any rank, regardless of his own; also, on rare occasion, a bishop will allow a priest to tonsure a monk or nun into any rank.

Eastern Orthodox monks are addressed as "Father", as are priests and deacons in the Orthodox Church; but when conversing among themselves, monks in some places may address one another as "Brother". Novices are most often referred to as "Brother", although some places, e.g., on Mount Athos, novices are addressed as "Father". Among the Greeks, old monks are often called Gheronda, or "Elder", out of respect for their dedication. In the Slavic tradition, the title of Elder (Slavonic: старецъ, Starets) is normally reserved for those who are of an advanced spiritual life, and who serve as guides for others.

Nuns who have been tonsured to the Stavrophore or higher are addressed as "Mother". Novice and Rassophore nuns are addressed as "Sister". Nuns live identical ascetic lives to their male counterparts and are therefore also called monachai (the feminine plural of monachos), and their community is likewise called a monastery.

Monks who have been ordained to the priesthood are called hieromonks (priest-monks); monks who have been ordained to the diaconate are called hierodeacons (deacon-monks). A Schemamonk who is a priest is called a Hieroschemamonk. Most monks are not ordained; a community will normally only present as many candidates for ordination to the bishop as the liturgical needs of the community require. Bishops are required by the sacred canons of the Orthodox Church to be chosen from among the monastic clergy.